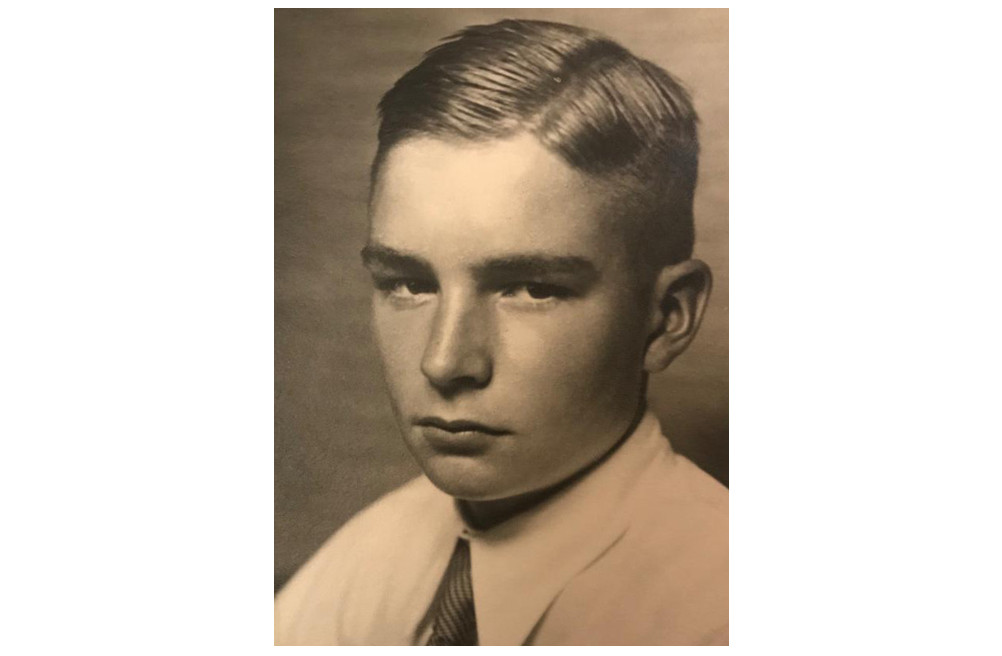

Jörg Watzinger has already been dealing with the history of his family during National Socialism for a long time. His father Dr. Karl Otto Watzinger survived the Dachau concentration camp. For his mother Marie, the persecution of her son resulted in a dramatic deterioration of her mental health. Both became victims of the NS regime. Now Jörg Watzinger’s gaze is directed towards his uncle Jörg Dietrich, his mother’s brother, after whom he was named. Jörg Dietrich had himself flown to Stalingrad in autumn 1942 and was considered missing since the beginning of 1943. From 1940 on he was already deployed as a soldier in other parts of the Soviet Union and in France. Before that he was a leader of the Hitler Youth until his graduation in 1939. In the following, Jörg Watzinger describes how the story of his uncle also affects his own life and which questions arise for him from it.

My mother, born in 1922, and her brother Jörg Dietrich, who was one year older, were very close to each other. Their two big sisters were noticeably older, born in 1913 and 1914.

© Private property of Jörg Watzinger

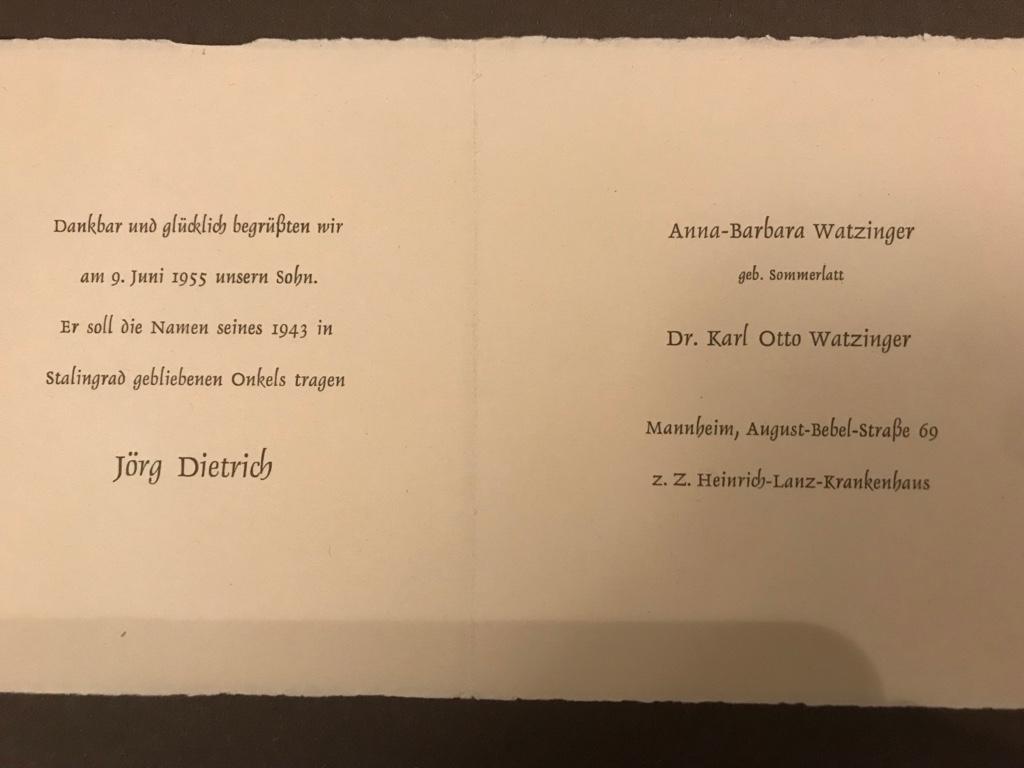

He was present when I was born, even though he was already dead. The birth announcement said:

We welcomed our son gratefully and happily on June 9, 1955. He shall bear the name of his uncle who remained in Stalingrad in 1943

Jörg Dietrich

© Private property of Jörg Watzinger

The other Jörg

Who was my uncle? I often asked my mother about him, until the old age of 90. She didn’t say much. He was a leader of men. An admiring tone, a transfigured look.

My grandmother (1881-1972) put together a portrait of her son’s life after his death. It also contains his field post letters. She writes about her 12-year-old son:

If Hitler had been torn from his heart, one would have run the risk of having torn out all his ideals too.

That was in 1933, before the Hitler Youth became obligatory.

© Private property of Jörg Watzinger

My grandfather Arthur Sommerlatt (1881-1971) wrote annual reports from 1946-1951, in which he reflected his thoughts on politics, economics and family. On the death of his son he writes in 1950:

He died in full accordance with his ideals, an enviable death.

How did it come about that their 12-year-old son became a convinced Hitler supporter? My grandparents belonged to the Christian youth movement: no alcohol, no sex outside of marriage, the biblical tradition was a central, vivid, daily level of reflection for them until old age. They were critical of the appropriation of the youth by the Nazi state. For them, parents and the Church were the natural authorities for young people. They also discussed this with the NSDAP local group in Augsburg, which earned them the file note:

The Sommerlatt family is morally contaminated by Christianity, a hopeless case.

Being young as an excuse?

When I asked my father, who had been a political prisoner in Dachau concentration camp for three years, about my uncle, he expressed understanding for his wife’s brother. He said that he was still young and seducible.

© Private property of Jörg Watzinger

My uncle was a leader of the Hitler Youth until his graduation in 1939. A photo shows him with Hitler Youth comrades on holiday in Croatia. After graduating he joined the labour service. Then he wanted to take up an officer’s career. In 1940 he complained that he had not been drafted immediately. He then came to France as a simple soldier, without combat.

© Private property of Jörg Watzinger

© Private property of Jörg Watzinger

In 1941 he was in combat duty during the invasion of the Soviet Union. His leg was shot through by their own artillery just outside Minsk. He could no longer be used on the weapon.

He used the time in the military hospital and afterwards to deepen his knowledge of the Russian language. At that time it was still planned to lead Russia as a colony under German administration after the conquest.

© Private property of Jörg Watzinger

In autumn 1942, against the advice of the doctor and without consulting the family, he had himself flown to Stalingrad.

He wanted to support his trapped comrades with their escape as a translator of Russian radio messages.

At the beginning of 1943 his shelter was conquered by Russian soldiers. His comrade went up with raised hands.

My uncle stayed behind. Whether he froze to death or gave himself the last bullet, as indicated in the last field post letter, remains open.

A grieving family

In 1950, he was declared missing. That year my grandparents had been able to speak to the soldier who had spent the last hours with him. My grandparents led the Protestant congregation in Friedberg near Augsburg from 1946 to 1951. There they organized a church memorial service for him.

My Aunt Ursel felt partly responsible for her brother’s untimely death all her life. She had encouraged him to become a soldier. His mother’s preferred career choice would have been doctor. As my aunt put it, it had been important to her to get her brother away from his mother’s coattails. When she was older, my aunt commented on his decision to be flown to Stalingrad like this:

Those who wanted to know, already knew in 1942 that the war would not end well. Jörg Dietrich saw no perspective for himself as a Nazi and as a war-disabled person for the time after the Nazi dictatorship and considered the “heroic death” as a suitable option for himself.

Rossoschka

When the German war cemetery Rossoschka near Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad) was rebuilt at the end of the 1990s, my uncle’s name was also written on one of the large granite blocks. The photo of it was very important for me. The memory of a “ghost” had finally found a place. I have not yet realized my plan to go there.

Instead, I became increasingly concerned with my mother’s family and the question of their role during the Nazi period. In 2018 I took part in the seminar “NS-perpetrators in the family” at the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial. One exercise was important for me there: we painted on a biographical time beam, in which phases of life the Nazi past of our family played an important role. For me it was directly after the birth. I had the image in my memory that when my mother’s family bent over my cot, they looked down on me with sadness rather than with joy for (my) new life.

That was an important impulse. I had rather come here with historical questions: What exactly did my uncle do as a Nazi? What are the definitions of Nazi perpetration? Was he a Nazi perpetrator? Had he shot defenseless people or caused their death in any other way? Now there was a new perspective, the existential, emotional question: How did my mother’s mourning for her brother affect me? What do I do with my grieving mother?

Becoming aware of emotions

Two trauma therapy sessions with Dr. Katharina Drexler helped me in this matter.

In a meeting on behalf of my mother, I went back to the situation that was too much for her at the time. The death of her beloved brother, who had left without saying goodbye, who died far away in the cold, caused her to close her heart. The beautiful emotions she shared with her brother in childhood and youth were no longer accessible. It was as if a book whose story begins beautifully is closed at a dramatic point and remains closed forever. The memory only revolves around the bad end. She herself was not aware that she was so cut off emotionally. I often found her emotionally unreachable, repellent like Teflon. In the session she could sense herself being closed and plan to open her heart again.

In another session, as a newborn, I went back to the situation in my grandparents’ garden. My father had become depressed after my birth and was under clinical treatment. My mother took me back to her parents. They had built a prefabricated house in a beautiful and large garden in Willsbach near Heilbronn in 1951. In itself a really beautiful environment to arrive in this world. But the adults were all distant. Nobody took me in. The frozen grief for the son and brother stood between us. Very irritating for me as a little boy. I was kept at a distance. Only through a person who took me in could the sense of “it is beautiful” be felt in the session. I also realized that this distance was not my problem, I was not the cause. It was the problem of the adults. They had not yet got over the death of their son and brother.

NS war crimes in the Soviet Union

So much for the inward view of how my uncle’s Nazi perpetration affected me as the 2nd generation within the family. In addition to the emotional legacy of my mother, there is also the other perspective: What did the Wehrmacht and the subsequent Nazi occupation in the Soviet Union do? What exactly did my uncle do as a Wehrmacht soldier? Was he involved in war crimes? This requires archive inquiries, which I still have in front of me.

As a result of the Second World War, 30 to 40 million people lost their lives in the Soviet Union alone. Even if my uncle, as a soldier in the Wehrmacht, only fired at other soldiers, he cleared the way for the racist Nazi occupation policy, under which the murder of Slavs, Jews and Communists was not considered a crime. And he took part in this war in the full conviction that Hitler was doing the right thing.

My view on the human, cultural and material devastation in the Soviet Union began with a visit to the touring exhibition “Malyj Trostenez, a place of extermination” in Frankfurt.

At a panel discussion in Hamburg, a historian sat next to me. She talked about how her great uncle, who lived in Minsk in 1941, was the only member of the Jewish family who escaped the murder of the Jews by the German occupation. He was 16 years old at the time. That is when what the history books call the Holocaust and the war of annihilation became tangible to me as something that happened between people and continues to work between people.

Regarding this I found a paragraph on the website of “NS-Family-History” (NS-Familien-Geschichte), which will certainly play a role for me in the future:

The other side are the families of the victims. For them, the destruction, torture, deportations, murders for which our family members were responsible are everything but the past. Quite the contrary: these family traumas still play a role in the lives of many descendants to this day. It is important for the relatives of the victims that we take note of the suffering caused by the perpetrators.