© Private property of Maria Grazia Gori Casati

Maria Grazia Gori Casati grew up without getting to know her father Italico. He died in a satellite camp of Neuengamme concentration camp in April 1945. In 2017, 73 years later, Maria and her husband Mauro decided to travel to Germany, to the places her father was imprisoned by the Nazis – Dachau, Neuengamme and Banter Weg IV.

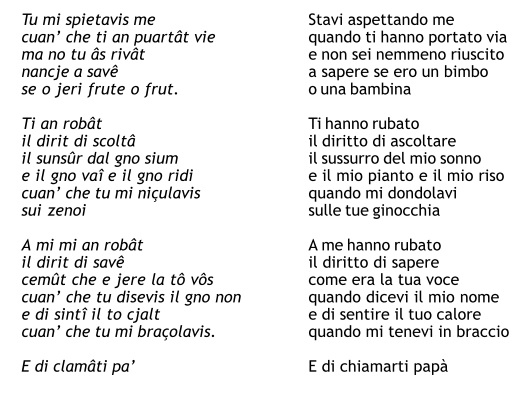

In the following, Maria writes about her father’s history and the couple’s emotional journey to the beloved father’s past. Maria and Mauro also decided to contribute a poster in remembrance of Italico Gori to the Space to Remember, including a poem written by Mauro in Friulian and Italian, that you can read at the end of the article.

I never knew my dad Italo. When I was born, in January 1945, he wasn’t there. The Nazis had taken him away to a concentration camp in Germany.

For many years I did not even know much about his death. I only knew what my mother had told me, and that was what the telegram from the International Red Cross said, that arrived eight months after the end of the war:

Date of death: April 1st 1945, Cause of death: Dysentery

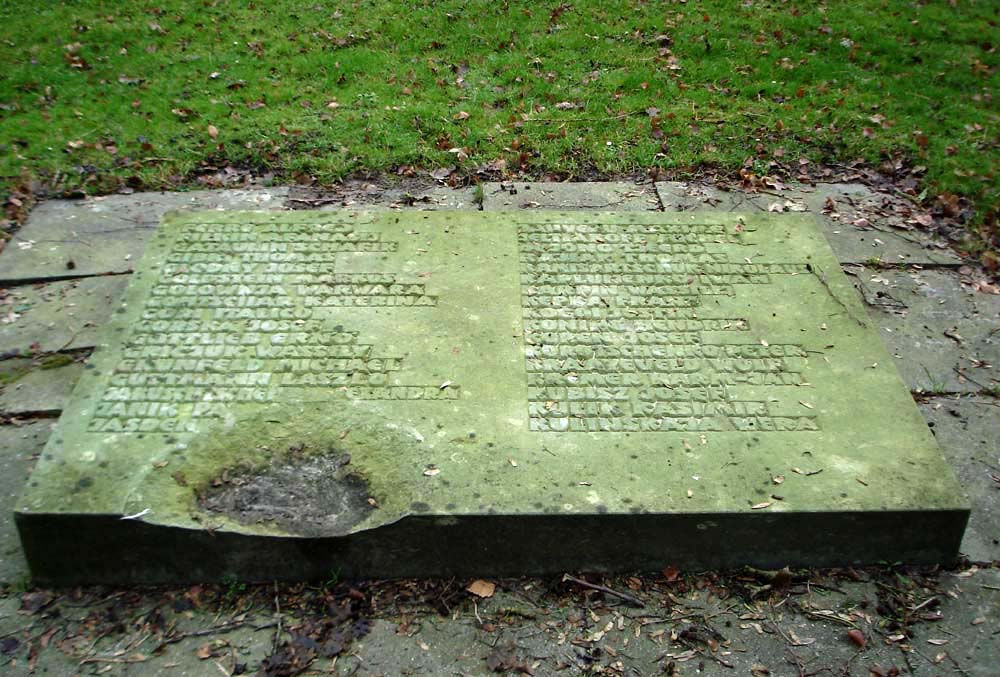

But how did he, Dad, get there – to Germany? How did he die? Where was he buried? At the ANED, the National Association of Italian political deportees, they did not know. In the book that collected the official lists of the deportees it was written only that he had ended up in a concentration camp in Northern Germany: Banter Weg IV, in Wilhelmshaven, a satellite camp of the main one in Neuengamme, south-east of Hamburg. Concerning his burial, it was better to put one’s heart at peace: there was a monument dedicated to the victims of Nazism and nothing else. My father’s body was missing – like those of thousands of other deportees.

So, for a long part of my life, my dad Italo was just a name typed on a yellowish sheet of paper, the worn out photo of him on the day of his wedding with my mother Anita, and ashes scattered in the fields of Germany.

© Private property of Maria Grazia Gori Casati

In short, an abstraction: in my childhood he seemed to me as a sort of charming prince – al are tant biel, my mom told me, he was so beautiful … Over the years, that abstraction has become a deaf and indefinable void. But in any case I lived with it.

The impetus for an important journey

Until three years ago, when my nephew Jacopo asked me to go to his school to tell the story of his great-grandfather: there was the Memorial Day and he had let slip that his grandmother’s dad had also been deported to Germany and that maybe she could tell something.

But how do you explain an abstraction?

I didn’t go to Jacopo’s school, but his request awakened the desire in me – but perhaps I should say anxiety – to give body to the void that had accompanied me all my life. From that moment on, a journey began that would take me, after 73 years, to find my father’s grave in Germany and to rebuild some scraps of another journey:

The one started by Italico Gori on September 29th, 1944 in Nimis, when the Nazis – before burning down the village that had dared to rebel against the occupation and establish the Free Zone of Eastern Friuli – snatched him from his family, from his job, from his wife Anita, and from me not yet born. They pushed him and fifty other fellow villagers by force onto a cattle wagon to Dachau and from there to Neuengamme. A trip that would have ended on April 1st, 1945, in Wilhelmshaven, a few days before the arrival of the Allies.

On the net in search of his tracks

I did the first research together with my husband Mauro, on the net. On the website https://dimenticatidistato.com we found a list of 1,234 civilians that got deported for political or racial reasons to various concentration camps including Neuengamme, to which Banter Weg IV of Wilhelmshaven belonged as a satellite camp. There was also Dad’s name, his prisoner’s number, place and date of death. But above all there was an indication:

“Burial place, Aldenburg”

Burial? Aldenburg? Where would this Aldenburg even be?

Searching the net, it is easy to find out that it is a Wilhelmshaven cemetery. At this point, we click on an icon and we are faced with a startling image: The memorial stone is called “Aldenburg Cemetery Memorial”. On the plaque it says “The victims of National Socialism”. Will this be the monument they told me about so many years ago?

Always on the net, let’s try to find “Alter Banter Weg”. It is a long, narrow lane that leads to the canal that runs along the southern part of the city. At some point, a marking appears with the words “KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme” – Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial. A zoom gives a glimpse of the profile of some foundations, they appear to be those of two barracks. Is this where my dad Italo lived during the last months of his life?

© Private property of Maria Grazia Gori Casati

We ask for news from the Memorial’s archive. Yes, they reply, Italico Gori arrived here on 22nd October 1944, coming from Dachau. From here, he was then transferred to Wilhelmshaven, to the Banter Weg IV camp, in the service of the arsenal of the Kriegsmarine, the German navy. He died there on April 1st and was buried two days later in the Aldenburg cemetery. For more information about the tomb, it is best to ask the cemetery directly.

With my heart beating fast, I write to the cemetery: “Is Italico Gori’s grave there?” The answer arrives in two hours: “Yes, your father’s grave is here.” Attached is the photo of a tombstone: In the row on the left, the name Gori Italico is the ninth from above. What an emotion!

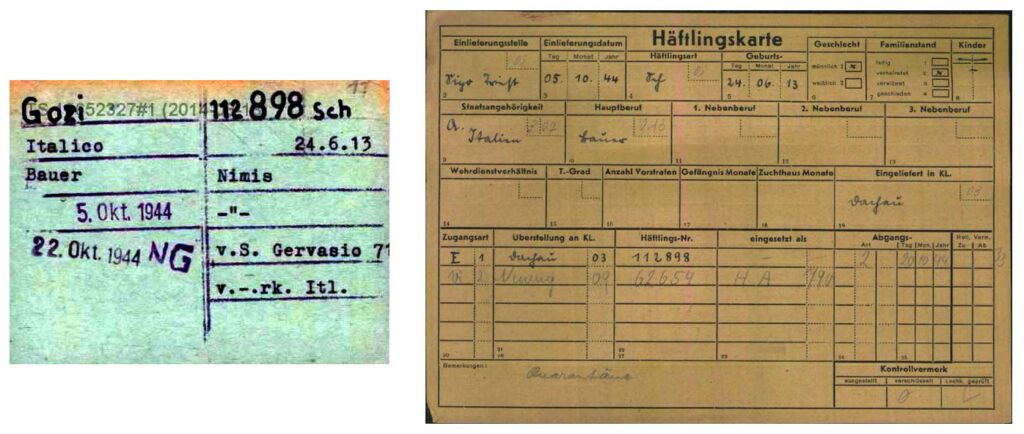

That tombstone in Aldenburg cemetery is the first real thing that testifies to my father’s passage to Germany. The second, even more personal, is the card they send me from Dachau’s archive. The surname has been corrected: Gozi and not Gori. There are the arrival dates in both Dachau and Neuengamme, work (“Bauer”, farmer), date and place of birth and residence. The abbreviation next to the prisoner’s number “sch” indicates the category “Schutzhäftling”, prisoner in protective custody. What a euphemism!

© Archives of Dachau and Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorials

In the one compiled later in Neuengamme, where he was transferred to with most of the group of deportees from Nimis, he has now become only a number: 62654.

In Neuengamme, the Nimis group is dispersed. When he arrives in Wilhelmshaven, in the camp of Banter Weg IV, blown by the icy wind of the North Sea, my father is definitely alone.

Trampling the earth he had trampled on

The mist was beginning to clear. But so many questions were still unanswered! When and why had my dad been transferred to Banter Weg IV, he alone among all the fellow villagers? Had he really died of exhaustion and dysentery, as the official records reported? Had he really been buried in Aldenburg two days later? Who had put his bones and those of 33 other companions under that big stone, and when?

© Private property of Maria Grazia Gori Casati

Reading Valeria Morelli’s book “Italians deported to extermination camps” has put us in front of a shocking reality. The reality of the mass graves dug near the concentration camps for the deportees killed during the marches and through the bombing that were buried quickly towards the end of the war. In one of these pits, exhumed by a French Mission a few years after the end of the war, together with the bodies of many French deportees, those of 14 Italians were also found. My father’s name is the last on the list.

The more I knew, the more grew the need to give body to the images seen on the computer screen and to the stories reconstructed only with the imagination. I felt the need to retrace the traces of that journey made by my father 73 years earlier, to trample the same land that he had trampled.

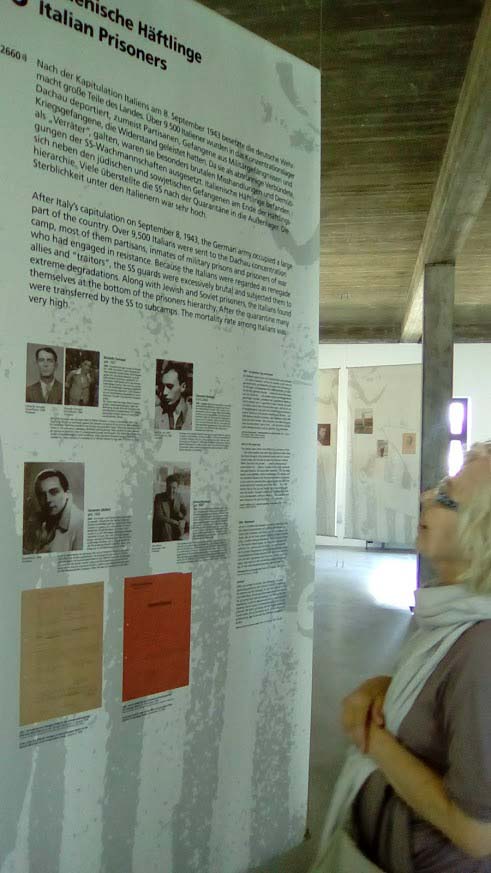

In June 2017, together with my husband, I redid my father’s journey in Germany. We crossed the gate of the Dachau camp with him, we stopped at front office where they had filed him, and then we saw the “barbers”, the showers, the concrete floor, the gutters, the striped uniform distribution, a strip of fabric with his number and a red triangle with a white “I” that he had to sew on the jacket, who knows how.

The next stop would have been Neuengamme. Instead, we sling towards the North Sea, to the end of his journey, to what was left of the camp of Banter Weg IV, where he died. A place half hidden among the reeds, which immediately seemed too small to us: Where could there be four long barracks, an appeal square, the guard posts? I stubbornly looked for the infirmary where he could have spent his last hours, and I imagined for a moment that he had thought of me. I stole a handful of earth to take home, to put it next to his tombstone in Nimis.

© Private property of Maria Grazia Gori Casati

On June 22nd, two days before the anniversary of what could have been his 93rd birthday, I finally touched his grave in the Aldenburg cemetery. And it felt as if the circle had closed. At that moment, I did not care anymore if my father was brought here a few days after his death or several years later. My dad was there, beneath this stone. And there, with him, a piece of me remained.

When we arrived in Neuengamme, the emotional charge that had accompanied us up to this point dissolved into a more peaceful feeling. We felt that the land that had been the scene for the last months of my father’s life had become a bit ours too. We still feel it. The human warmth that we have always felt from everyone, first in our virtual journey and then during the real one in Germany and, in particular what the young women who guard the memory of the deportation to Neuengamme have communicated to us, has opened a breach in the monolithic vision we had of Germans and brings us closer to them than we could have ever imagined.

Poem for Italico Gori

© Mauro Tosoni

You were waiting for me

when they took you away

and you didn’t even know

if I was a boy or a girl

They stole your right to hear

the whisper of my sleep

and my tears and my smile

when you swinged me

on your knees

They stole my right to know

what your voice was like

when you said my name

and to feel your warmth

when you held me in your arms

And to call you dad