On April 4, 2018, Wim Aloserij proudly presented “his” book to Sybrand Buma, the then parliamentary group leader of the Dutch party “Christen-Democratisch Appèl”. The venue was the Kamp Amersfoort memorial, where around 80 guests and family members had gathered. Buma humbly accepted the book, entitled “The Last Witness” (literal translation from Dutch, English title: The Last Survivor), and told those present about his grandfather. Like Wim Aloserij, he was deported from the Amersfoort camp to the Neuengamme concentration camp, but unlike Wim, he did not survive. Buma writes about this in his impressive foreword. He called the book a tribute to the victims of Nazi terror and a tribute to Wim himself, who seventy years later was ready to tell his whole story.

© Krake

I was the chosen one to spend a year with the main character of the book – a year full of recording the stories told by Wim and researching in international archives. The many documents I found there opened new doors for Wim, and a joint visit to the memorials of the Husum-Schwesing and Neuengamme concentration camps completed the picture.

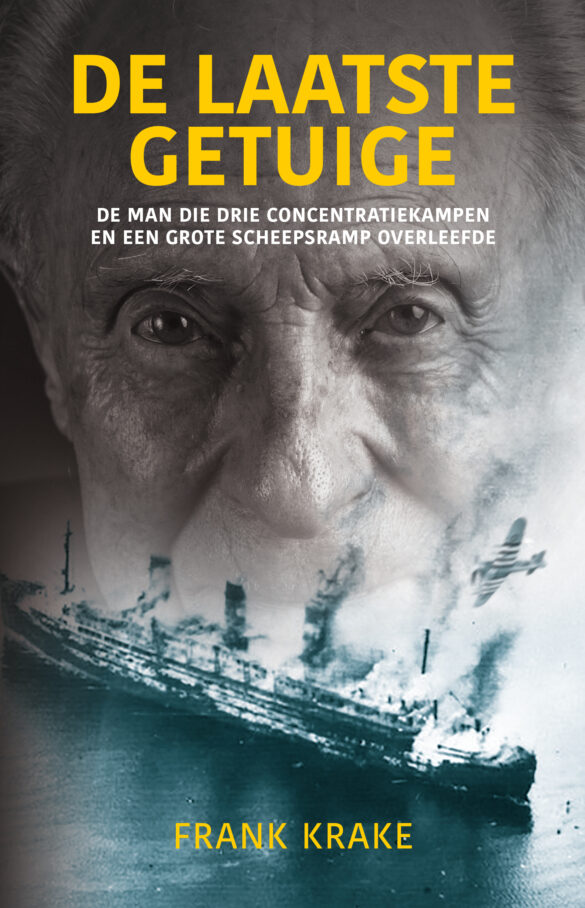

Wim Aloserij was the man who survived three concentration camps and the bombing of the Cap Arcona in the Bay of Lübeck. At the end of his life, after decades of silence about all these horrors and privations, he told me, a complete stranger, all the details of his wartime past. Wim said it had to travel around the world. We started in the Netherlands.

So we hit the road. In the weeks following the book’s publication, we toured bookstores and venues, from Tilburg to The Hague and from Putten to Almelo. Everywhere, full halls and audiences that looked spellbound at this unique man who survived it all. When Wim entered the room, silence fell automatically. And when he began to tell his story, you could hear a pin drop. The visitors listened breathlessly to his narration, and he was not forgetting to add a light-hearted remark now and then. He was a born storyteller and played with his audience. Whether there were 50 or 300 people in the audience, Wim didn’t care. He was pleased with the audience’s sincere interest in his war experiences. And he enjoyed the standing ovations he regularly received. Afterwards, he threw himself wholeheartedly into signing the books for the guests, and had a kind word for everyone.

Four weeks after the presentation of the first book in Amersfoort, Wim traveled by plane to Hamburg to participate in the commemorations in Neuengamme and Neustadt. But he did not return. Only ten kilometers from the concentration camp where he was imprisoned, he never woke up after a short nap. The book was finished, his mission accomplished.

© Krake

Ironically, his sudden death meant a new sales impetus for the book. Wim must have laughed at this twist of fate. The book spent no less than 24 weeks on the Dutch bestseller list in 2018. More than 50,000 copies were sold.

I went on alone to spread Wim’s story with the conciliatory message in bookstores and halls in all parts of the country.

The two most frequently asked questions were whether the book would be made into a movie (that’s in the stars) and whether it could be translated. The latter question was on my mind. From past experience, I knew that there was only a chance of translation if a reputable literary agent represented an author’s work abroad. Once, at my own expense and risk, I had my first book, Master of Disaster, translated into English. Years later, I was ten thousand euros lighter and one illusion poorer. The book is still available on Amazon.com and was sold only twelve (!) times in five years.

Therefore, I needed a literary agent, a professional who could submit the manuscript to a foreign publisher. I put a lot of time and energy into the process and was happy when I signed a contract with an agent who was known as good and professional on the market. Together we worked on a summary and material to promote “The Last Survivor” to foreign publishers. So we were able to get to work.

Two years later, we were still empty-handed. No one had shown interest, the agent said, which was depressing. But I refused to throw in the towel. Wim’s story had to go around the world. From the time I had just started writing, I knew another literary agency called Sebes & Bisseling (S&B), the best in the Netherlands. At that time they showed no interest in my work.

In the meantime, sales had steadily increased and we had sold around 60,000 copies. That’s really a lot of books, as S&B also realized. If we were going to do business together, there was more to settle than just the contract. The most important prerequisite for success was some changes to the content. There had to be a new prologue that would draw the reader into the book with a bang. In other countries, an unknown author doesn’t have time to work toward a climax, you just start with it. But how do you go about it? Then it’s good to be able to work with an experienced editor. Enno de Witt edited all six of my books, and with his help we achieved the necessary big bang. And abroad, of course, the name Sybrand Buma means nothing to anyone. His preface was dropped for that reason. Finally, I had to write an author’s letter. An explanation of why I wrote the book, what was so special about it, and why this story should continue to be told. That was the easiest part; I’d had it in my head for years.

In November 2020, the time had finally come: The new literary agency could start their work. Exciting! Within a month, an extremely enthusiastic offer came from one of the biggest English publishers: Orion Publishers. They wanted to distribute the book in every English-speaking country in the world except the United States. French, Italian, and a number of Eastern European publishers soon followed. They were all reputable publishers who wanted to publish the book in their local area. S&B signed contracts with a Hungarian, Serbian, Slovenian and Romanian publisher. The icing on the cake was added six months later by an American specialist in war books, followed by Russia’s largest publisher, which will publish the book in the Russian-speaking world. Of course, I can’t wait until Putin can read in his own language that war leads nowhere and that the world is too beautiful and life too short to hate each other (Wim’s words).

The year 2021 was dominated by the preparation of a high-quality English translation. This would form the basis for the Eastern European and American editions. The French and Italian versions would be translated directly from Dutch. Translation is a profession in its own right, for which there is special training in the Netherlands, and I realized why. Haico Kaashoek has dedicated himself to this honorable task and created a gem of an English version of “The Last Survivor.” I really underestimated how much time and dedication went into such a work. Together we thought about some fundamental decisions that had to be made. What to do with the German commands in the book like ‘Raus, Raus, Schnell, Schnell’ or with the job titles of the SS men? Or with a word like ‘Stubendienst’? And is the ‘Tweede Kattenburgerdwarsstraat’ retained, or does Wim simply go to school via “a side street” in the English version? After six months, the manuscript was finally sent to the editor at Orion Publishing. After a careful reading, it came back with a new document full of notes, questions and deleted passages (too Dutch). With the good will of all involved, we got it done, and what was left was a manuscript that all three of us were happy with.

© Orion Publishing

Parallel to the textual fiddling, Orion’s design department worked at full speed. The result was a beautiful cover. Quite different from the Dutch cover I had designed myself, which showed Wim’s face in close-up with a burning Cap Arcona underneath.

It was also decided not to translate the title one-to-one (“The Last Witness”), but to choose the title “The Last Survivor” rather for the English audience.

Just before the launch, we were treated to an aha moment. The world-famous best-selling author Jonathan Dimbleby reacted to our manuscript. He had read it and we were allowed to use his words as a quote: “This is an extraordinary biography, important and unforgettable”.

With these words, Wim’s war story is now traveling around the world.

© Krake

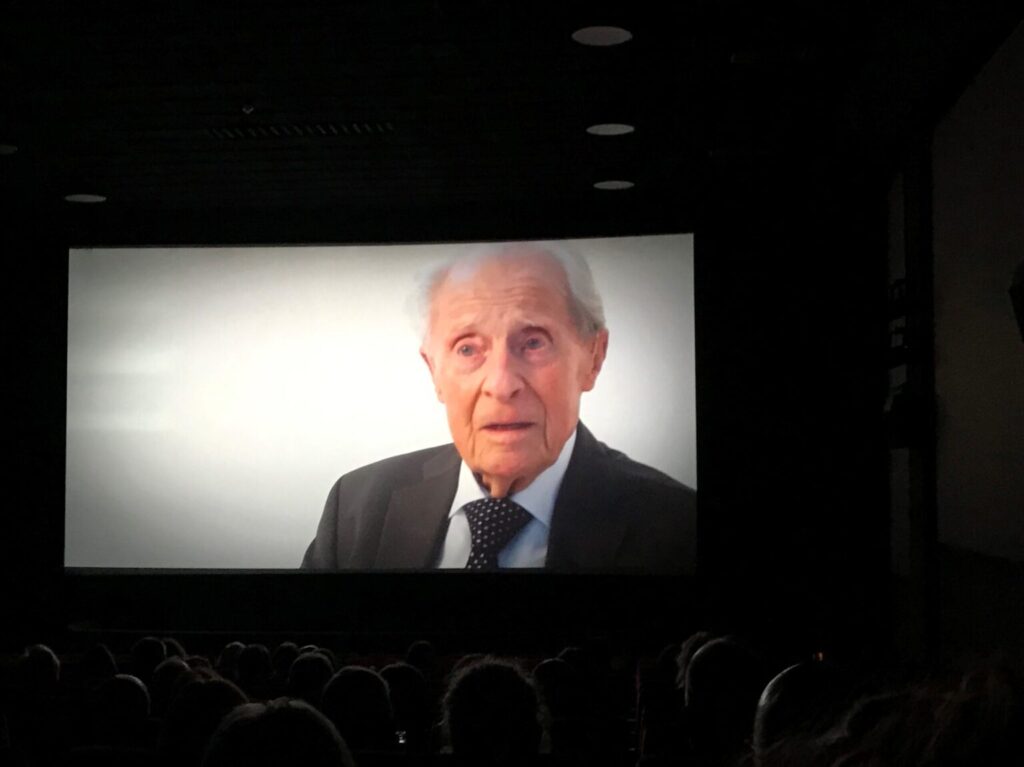

On May 8, 2022, the German Liberation Day, I stood on stage in front of a packed cinema in Husum. At the invitation of the Husum-Schwesing Memorial and the district of North Frisia, I had the opportunity to speak to those present, most of whom were citizens of the town. We had just seen in this cinema a documentary film lasting more than half an hour about the visit of Wim Aloserij to the Husum-Schwesing memorial. This historic visit took place in November 2017, six months before Wim’s death. I had walked with him around the camp grounds and he told me about his experiences, which had come back to him on the spot. What followed was an interview that was supposed to last no more than an hour. In the end it became three hours and Wim did not stop talking in front of the camera. The result is a beautiful documentary film about the last survivor of the Husum-Schwesing camp.

I talked about my experience with Wim, about the wonderful year I had spent with him, and about the success of the book, which will be published in nine other languages in addition to Dutch. Then the question came from the audience whether the book would also be translated into German. I looked around the room and waited a moment before answering, “No, no German publisher has shown interest.”

The room remained silent for at least a minute. Surprisingly quiet. If one could have crawled under the chairs, a large part of those present would have done so. Slowly a murmur began, which gradually swelled into a babble of voices. No one dared to ask another question, and the official part of the meeting was over.

Afterwards, we toasted the successful film premiere with champagne in the foyer. With a heavy heart, one guest after the other contacted me. No German translation? How was that possible? Disbelief, disappointment, apologies and even anger about it surfaced. Within fifteen minutes, this turned into fighting spirit, solution-oriented proposals and concrete commitments. The citizens of Husum, the volunteers of the local memorial and the administration of the district of North Frisia would not allow this to happen. They would not stand idly by and watch what happened eighty years ago. They had the firm intention of joining forces and ensuring that a German translation would be published.

At the time of writing this article, we are working intensively on it, and I am also making a contribution. The goal is to present the book no later than 2024, on the 80th anniversary of the Husum-Schwesing concentration camp.

Perhaps in the same movie theater, in front of the same people who were recently outraged, so that we can all say: “Never again.”