In her fourth article about her visit to Germany in 2018 Roslyn Eldar describes her visit to Muna Lübberstedt, the former satellite camp of the Neuengamme concentration camp, where her mother and other family members had had to do forced labour in an amunition factory. Her article illustrates the importance of family history across the generations and the value of the work of volunteers dedicated to a meaningful culture of remembrance.

Oh that my head were waters, and mine eyes a fountain of tears, that I might weep day and night for the slain of the daughter of my people.

Jeremiah 8:23

Celebrating a birthday 73 years after liberation

Friday, 4 May 2018, was the day I had been waiting for. We were to go on a private tour of Muna Lübberstedt, the ammunition factory where my mother and her relatives had been prisoners when it was a satellite camp of the Neuengamme concentration camp. This was the culmination of almost two years of research. When I started this investigation I never imagined it would result in this family pilgrimage, a pilgrimage to such an unholy destination.

My cousin Mindu, her daughter Nicola, her grandson Alex, my son David and I had breakfast together at our hotel in Hamburg. It was Mindu’s 89th birthday. She was to celebrate by visiting the ammunition factory that she had been imprisoned in for eight months between 1944 and 1945. It was a celebration of her survival.

At 9.30 a.m. a mini bus came to collect us with Mindu’s survivor friend Barbara Lorber and her grandsons already on board. We also travelled with the two minders and a cameraman who all had been assigned to us by the Neuengamme Cocentration Camp Memorial. It is about a two-hour drive to Lübberstedt from the centre of Hamburg.

The Power of Survivors’ Testimonies

During the bus ride to Muna Lübberstedt there was much chatting and excitement between the various offspring, the two survivors and their minders. However, the atmosphere became more sombre when we reached the Community House in Axstedt, which is a five-minute drive from Muna Lübberstedt. About 20 School children around the age of 15 soon arrived with their teacher to hear both Barbara and Mindu talk about their experiences in Auschwitz and the satellite camp.

You could have heard a pin drop as the two women spoke. As Barbara speaks German fluently she did most of the talking. Both survivors cried at times. Some of the students cried too. It was an impressive, authentic history lesson.

Hartmut Oberstech, who I had met after the multigenerational discussion held on May 2, was also at the Community House. He had taken the day off work especially for this event and went out of his way to bring us lunch after the talk.

We ate in the Community House with school teachers and other members of the voluntary association “MUNA Lübberstedt“, including Barbara Hillman, Erdwig Kramer, Rudy Kahars, and Ilsabe and Ulrich Tienken. We greatly appreciated their hospitality.

Walking in freedom where my family members had been slave laborers

Finally, we were driven to the former ammunition factory. The group consisted of eight family members, several volunteers from the Muna association, two minders, one cameraman and one journalist.

Front row L to R: Nicola Foster, Mindu Hornick, Barbara Hillman, Barbara Lorber and Barbara Lorber’s grandsons.

We arrived at a home that was built on part of the ammunition factory ruins. The property had been sold to a family in the 1950s before its historical significance was understood. On this private property stand the remains of one of the air raid shelters used by prisoners and SS when the British RAF was bombing the area. The owners of the land are forbidden to tear this shelter down. This was the last time the owners would give permission for any tour to enter the former factory grounds via their home, so we were lucky to gain entrance to see this.

We walked around the outside of their home and garden area and then over green fields, to an air raid shelter. It was over grown with shrubs and dilapidated. The survivors did not recognise it. They recounted how towards the end of the war, they were crammed inside the shelter at night and had to sit on concrete until the air raid was over. They were exhausted from working and wanted to lie down and sleep in their barrack.

The memories came back

Barbara said one time she did not go to the bomb shelter, even though her mother begged her to. She remained in her barrack, exhausted and was lying in her bed when an SS female guard came to check and started to beat Barbara with a truncheon. Luckily, another SS guard came in, one who favoured Barbara, as she was a good singer for the morning march to work, so the beating stopped.

I recalled that my aunt Elizabeth Just had also told me she once hid in a cupboard in her barrack to avoid going to the shelter. She was also discovered by a female SS guard who beat her on the back with a truncheon. Unfortunately for my aunt, nobody interrupted this beating.

How to remember in the absence of original objects

We stood in the fields surrounded by forest just as my mother said. I realized how the forest provided protection against aerial reconnaissance. Once again it was perfect weather, with blue skies and shining sun. Hartmut explained where the other buildings would have been. Everything apart from this bomb shelter is gone – the prisoner barracks, the kitchen, the wash facilities, the roll call area, the bomb production area, all gone. The production facilities were blown up at the end of the war by the Wehrmacht to hide their crimes. Other buildings had fallen into disrepair and were torn down before their significance was appreciated. Just green fields that merged into surrounding forest remain, now preserved and not to be touched. At first I was upset there were no buildings to see but then I felt it was perfect this way. What mattered is that I had finally arrived and I was fortunate enough to do so with the actual survivors.

We walked from the air raid shelter towards the bomb production area, a walk the prisoners had had to do singing in German six days a week for eight months. I walked beside Barbara our arms linked. One of her grandsons was on her other side. Ahead of us were Mindu with her daughter and grandson. My son David was further ahead. We were surrounded by forest. It was still. We walked in freedom, safe.

Stories of survival

The prisoners’ routine was daily roll call at 5 am, followed by breakfast consisting of a brownish broth called “coffee” and four slices of bread per day. As the war progressed and supplies diminished it became four slices of bread per week. The prisoners then walked to work in step, singing in German, guarded by SS female guards. The walk to the production area was 1.5 kilometres, and to bunker storage area was 5 kilometres. The walk during winter was difficult, especially for those women who only had wooden clogs for shoes. Lunch was a soup at the factory. The work shifts were 10 to 12 hrs and the prisoners worked day and night shifts too. After their return to the barracks in the evening, there was another roll call followed by dinner of some bread and maybe some sausage or quark.

My grandmother Berta Ruttner had a job as a cook for the SS in the kitchen. She supplemented her family’s meals by stealing potatoes to help them survive. She did this risking her own life. The Luftwaffe paid two Marks a day for each unskilled labourer and the SS received this “pay”.

The work of the women involved filling, assembling, packing and loading bombs for the Luftwaffe, which resulted in serious damage to their health. The chemical fumes turned their hair red, and many of the women were struggling with lung problems.

My aunt who still lives in Melbourne had the job of pouring toxic bomb fluid into bombs without protective clothing. After Liberation she had surgery in Prague in the hospital for a perforated lung. She then spent approximately one year in the hospital. When she had recovered enough to leave the hospital, she spent another year in the Tatra mountains recovering in a private clinic called “Villa Dr. Szontagh” all paid for by her uncle Joseph Slyomovic. Mindu also spent six months in a clinic with lung issues post- war.

Mindu and Barbara commented that although they were still afraid and exhausted from their hard-physical labour, starved, beaten and humiliated, the selection for work from Auschwitz had saved their lives. The ammunition factory was not an extermination camp, and the air did not reek from the stench of burning flesh and bones. The camp had, at times, a human face they said, as some of the SS female guards were kind and tried to help the 500 Jewish female prisoners

Mourning the women who were killed

We returned to the mini-bus and were then driven all around the periphery of Muna Lübberstedt. The 420-hectare complex had comprised, at one stage of 22 filling buildings (that is where the bombs were filled with fluid) and 102 bunkers for storing ammunition, two 26-meter-deep wells for water supply, 30 kilometers of road and 7.6 kilometers of railway network.. In the parachute house huge parachutes were packed for the up to 1,000 kg heavy mines. In the powder mill explosives were recycled from faulty ammunition.

We drove through the main gate where the public tours enter and stopped at the bunker area where the bombs were stored, once again hidden from aerial view by the forest. Toward the end of the war, when no fuel was available to drive the larger wagons full with bombs to these bunkers, the slave labourers had to push the wagons. Two female prisoners pulled a wagon and two pushed it, heavy with huge bombs that they had loaded onto the wagons. Later they had to unload the bombs into the bunkers. Bunkers where the bombs where stored were very large and dark inside like a concrete cave. There were 102 bunkers covered with earth.

Prisoner Etel Jerkewitz was beaten because she was too slow and then, due to the beating, she was unable to work anymore. That evening the prisoners bought her body back to the barracks where she died.

Five women are recorded to have died in Lübberstedt, two of them from beatings and two from “illness” . In her DEGOB statement my mother noted:

The camp Commander changed every three months; the third one was very bad. Two women, who were sick and stayed in the room before roll call were beaten to death by him. We heard them screaming and whining; they died that evening…”

Of the 500 women transported to Muna Lübberstedt from Auschwitz, about 380 survived the war. Five prisoners had died in the factory camp. About 60 women had been transported to Bergen Belsen where maybe only 10 survived. Some died from starvation and illness on the ‘evacuating’ train. Approximlately 60 died when the train was bombed twice by the RAF in the last days of the war. The bombings occured in Eutin on the 2nd May 1945 and again near Plön on 3rd May 1945. The RAF mistakenly thought the train held only fleeing Nazis. Many prisoners were injured by these bombings. Some had head injuries. Others had to have limbs amputated.

Liberation by the Britsh army occured in Plon on the 8 May 1945 .

The perpetrators got away

In the early 1970s there were preliminary investigations by Germany into war crimes that were committed by the three Commanders and various SS female guards of Lübberstedt. The Prosecutor stated that war crimes had been committeed, but survivors had not given him enough information by to identify the perpetrators. There was a stay of proceedings by the Prosecution on 3rd October 1974.

The names of the victims shall not be forgotten

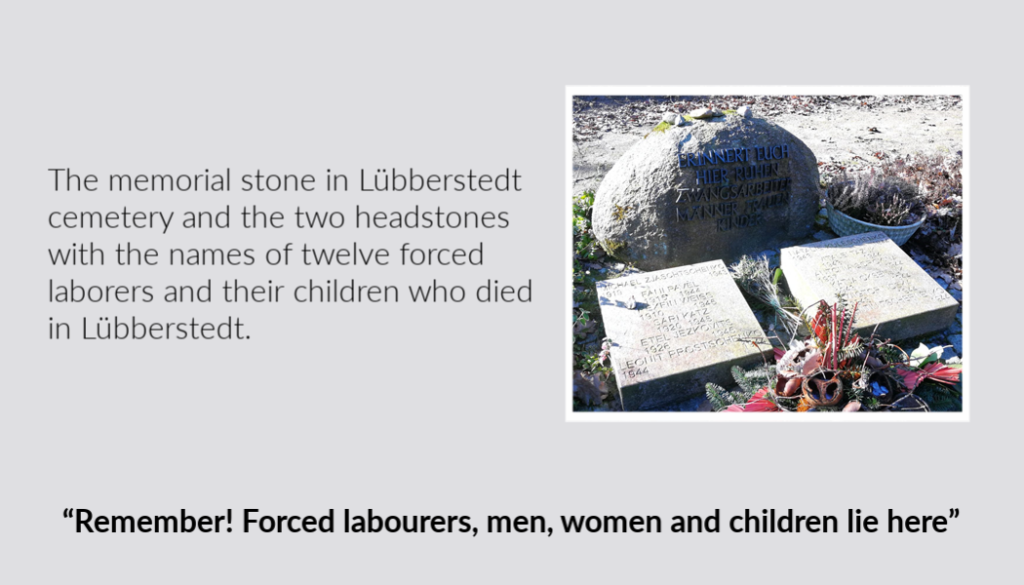

In Lübberstedt cemetery we visited the communal grave of four of the Jewish female prisoners who died in Lübberstedt. They are buried together with eight Russian Prisoners of War. Originally these 12 bodies were in separate, unmarked graves. However, in 1989 the Axstedt local authorities moved them to the current communal grave and marked it with a memorial stone. In 1997 the Lübberstedt voluntary group added two headstones, listing the names of the deceased prisoners so they have their dignity again.

As we stood around this gravesite, Erdwig Kramer said a heartfelt prayer:

At the end of August 1944, 500 Jewish women who came from Auschwitz were discharged from cattle cars at Lübberstedt railway station. They had to work hard in an ammunition factory. Here at Lübberstedt cemetery four prisoners (Fani Pavel, Ethel Jezkowitz, Sari Katz and Rexfin Weiss) found their last rest.

The grave of Babczu Bistricer is unknown. We want to remember the Holocaust victims who were persecuted and murdered as a part of the European population. The Nazis wanted to attack the God of the Jews and to annihilate His people. We want to stand up to preserve the memory of those crimes. Just like many of the survivors want this and as Elie Wiesel has demanded it in his book “The Forgotten”.

We Germans must not forget either what humans are capable of in certain situations. We must remember, do soul-searching and ask ourselves which prejudices deep inside us lead to such inhuman acts. Anti-Semitism and racism are still present. We must not allow that they humiliate and destroy human lives again in our country. Let us remember the victims in silence.

Celebrating life in spite of the scars torn open

After our return to Hamburg, Mindu’s daughter Nicola and her grandson Alex immediately went to the airport to return to the UK. Barbara Lorber and her family were leaving for Israel very early the next morning.

That left Mindu, David and myself. It was still Mindu‘s birthday so we went to a restaurant to celebrate in style, in stark contrast to the day’s events. We ended the meal with a mini cake and sparklers. I cannot imagine how Mindu was really feeling and how strange it would be for her to re-visit this part of her past.

Mindu Hornick celebrating her 89th birthday with David and myself. 4th May, 2018, Hamburg, Germany

The next day there was an article in the local newspaper Osterholzer Kreisblatt” about our tour of Muna Lübberstedt. The journalist quoted Mindu who had said:

“It is hard for us to come here and every thought of the time tears open the scars again. “

The article went on to say that the women give the talks to warn that such a thing should not happen again. Also, they wanted to show their families the place that had done them harm but had been their salvation.