Barbara Brix has been engaged in memory culture for years. In 2006 she began to deal with her father’s history during National Socialism in more detail than before. As a doctor, he was part of the so-called “Einsatzgruppen” (task forces) responsible for the murder of countless people in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Together with two descendants of Nazi persecutees and another descendant of a Nazi perpetrator (“Mémoire à 4 voix”), she gets invited to schools and cultural institutions in Germany and France. In the following article she reports on the contested “Memoria Histórica” in Spain and the events of the “Mémoire à 4 voix” on 3rd and 4th March 2020 in Barcelona.

Memory in the field of tension between history and politics

Every country has its own culture of remembrance – I only slowly understood this after I came to the French-Spanish border region in September 2007 with my experiences from 30 years of history lessons in Hamburg and the observations and encounters around the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial.

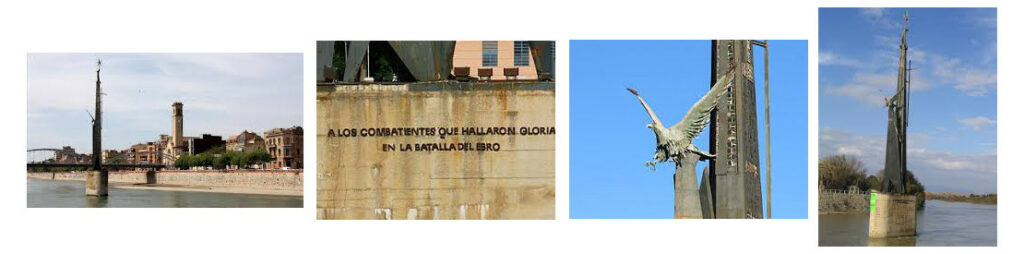

A year as an “Aktion Sühnezeichen” (“Action Reconciliation”) volunteer in the former internment camp Rivesaltes near Perpignan had made me aware of the differences between Germany and France. But that Spain and Catalonia, on the other hand, are wired differently again only gradually became clear to me. It was after I had completed four weeks of practical training in the Exile Museum on the border and in the “Memorial Democrátic”, the Catalan memorial institute in Barcelona and after a trip to the places of remembrance of the “Batalla del Ebro”, that legendary battle where in 1938, despite the almost superhuman commitment of the Republican Army and the International Brigades, the victory of the Franco putschists was sealed.

But I needed even more time to understand that private as well as public memory is not only shaped by the respective specific history of the country, but also by the willingness to be open, even self-critical towards it, or on the other hand, the intention to use or reinterpret it for political purposes.

Recently we were shocked by a message from Madrid. The right-wing city government, which is not in office for long, with the support of the extreme right-wing party VOX, is about to close a monument at the Eastern Cemetery, which is dedicated to the 2937 victims executed during the Franco era, and to tear off the name plaques. The monument had been erected by the former left-wing city administration, which had also ensured that numerous streets bearing names from the Franco era were renamed against the fierce resistance of the conservative opposition.

Dealing with the memory oriented towards the Civil War and the Franco dictatorship, “Memoria Histórica” is still an explosive subject in Spain. It leads to ever new legal regulations or corrections in all government formations, also in the provinces, depending on the political colour.

Obstacles for “Mémoire à 4 voix” in Spain?

© M. Casanovas

Jordi Font, the director of the Catalan Exile Museum, immediately confronted me with this argument when I told him about our German-French quartet “Mémoire à 4 voix”. It is composed of Yvonne Cossu and Jean-Michel Gaussot from France, whose fathers were deported to Neuengamme concentration camp as members of the Résistance and died shortly before the end of the war in the death camps of Sandbostel and Wöbbelin, as well as the two Germans Ulrich Gantz and myself, Barbara Brix. Our fathers held high posts in the so-called “Einsatzgruppen”. Those murder squads which, from 1941 onwards, murdered tens of thousands of Communists, Jews and mentally ill people after the Wehrmacht invaded the Soviet Union.

The four of us met at the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial and became close friends. Since 2017, we have been performing together in front of school classes in French-speaking countries, telling our different family stories, as well as about our friendship.

Jordi Font said he would strongly advise us against performing in Spain and even in Catalonia. Our project, which is designed to overcome the nationalist “hereditary enmity” of our fathers’ generation and sends out a message of reconciliation and tolerance, would not only be completely misunderstood, but immediately politically instrumentalized. The current political situation reflects the constellation of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) with hardly any change and is – due to the lack of discussions within the society – almost as irreconcilable as it is uncompromising.

Fights over the “Memoria Histórica”

This gave me a lot to think about, and indeed there are many examples in Spain that seem to support this thesis: we only need to recall the battles over the transfer of Franco’s tomb out of the the Valle de los Caídos (“Valley of the Fallen”), the national sanctuary of the Frankists.

Currently, in the city of Tortosa along the Ebro river, there is a bitter dispute over a monument erected in 1966 at the mouth of the river dedicated to Franco and the “glorious fighters of the Battle of the Ebro” (according to the inscription, see photo) that was inaugurated by Franco. The city fathers see no reason (after the most striking symbols of Frankism were removed a few years ago) to tear down the monument or even to put up an information board explaining the historical context.

© Heike M. Martinez

After the success of the “Audiencias Memoriales” in Catalonia – Jordi Palou also invites the “Mémoire à 4 voix” to Barcelona

So it was both a premiere and a courageous act when Jordi Palou, director of the NGO “A Peace Letter to the UN”, invited us, the “Mémoire à 4 voix”, to Barcelona a year ago. His organisation, together with the Pére Tarres Foundation, is committed to peace and justice through many projects.

One of these projects, the so-called “Audiencias Memoriales”, invites the descendants of victims or perpetrators of the Civil War parties to take a seat on the same podium. They have sometimes lived silently side by side in their village for decades. Now they are asked to speak in public, in front of their neighbours and the dignitaries of the community, about their family history and their view of the events of that time, and also they are asked to listen to the stories of others.

That’s what it’s all about: telling what has never been told in public in this way before, and listening respectfully. Not very spectacular, one might think. But, as Jordi Palou reports, this process can have an enlightening, complementary, healing effect. It can initiate surprising processes of understanding and encounter where fear, rejection and silence previously prevailed.

In some Catalan villages these “Audiencias Memoriales” have taken place successfully in recent years. They are currently on hold because the government has stopped financial support.

Jordi Palou was not discouraged by this. He included us, the “Mémoire à 4 voix”, in the series of events “Remembrance, Resilience and Overcoming Resentment during War and Dictatorship”.

On 3rd March 2020, we sat across from about 140 senior class students in Barcelona; on the evening of 4th March, there was a panel discussion at the Law Faculty of the University Ramon Llull. The host chair deals with Criminal law, Penal system, Reparation and Perpetrator-Victim-Mediation.

© Daniel Lagartofernandez

Against all warnings, our French-German dialogue between children from persecuted families and those from Nazi families met with a lively response from the audience. Many interested and moving questions were asked from the spectators until the official ending. The media echo was impressive: the two big daily newspapers “La Vanguardia” and “El Periódico” brought detailed interviews with us. The main TV channel of Catalonia TV3 interviewed us for the morning news broadcast and also showed many pictures of the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial.

Reasons for the silence

It is more difficult to estimate the deeper effect. Encouraged by so much approval, I took heart at the end of the panel discussion and asked the audience directly whether our modest attempt to send out a message of tolerance would be heard and understood in this still deeply divided country.

There was a lengthy silence. Then a woman raised her arm:

“Which reasons were there in Germany for the long silence after the war?”

Another of many possible answers to my question I received a week later. I was back in the south of France, in La Coûme, an environmental workshop for young people in the foothills of the Pyrenees.

Marta, the education officer, who actually comes from Catalonia, looked at me silently for a long time.

“Do you want an honest answer to your question?”

I nodded.

“The blame for the polarised situation and the silence of the past dates back to the 1970s, when after the death of Franco (1975) and with the introduction of democracy in Spain, an amnesty law was passed for the crimes of both sides and all parties agreed. This “pact of silence” also put an end to any critical examination of Franco’s coup d’état, the Civil War, and the 44-years long dictatorship. And so these topics disappeared from the school books.”

In this context and for more information I would like to recommend the movie “The Silence of Others” (Spain/USA, 2018). Among many other aspects, it also shows f.e. how the question of opening the many thousands of mass graves from the Civil War is still a political issue today and is treated differently depending on the governing party.

This article was published in the magazine freundeskreis aktuell No. 34 (april 2020).

Translation: Nathalie Döpken